Digitoxin

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Digalen, Digitaline, Digitmerck, others |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, Intravenous injection |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 98–100% (oral) |

| Protein binding | 90–97% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP3A4) |

| Elimination half-life | 7–8 days |

| Excretion | 60% via urine, 40% via faeces |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.691 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

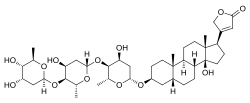

| Formula | C41H64O13 |

| Molar mass | 764.950 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Digitoxin is a cardiac glycoside used for the treatment of heart failure and certain kinds of heart arrhythmia. It is a phytosteroid and is similar in structure and effects to digoxin, though the effects are longer-lasting. Unlike digoxin, which is eliminated from the body via the kidneys, it is eliminated via the liver, and so can be used in patients with poor or erratic kidney function. While several controlled trials have shown digoxin to be effective in a proportion of patients treated for heart failure, the evidence base for digitoxin is not as strong, although it is presumed to be similarly effective.[1]

Medical uses

[edit]Digitoxin is used for the treatment of heart failure, especially in people with impaired kidney function. It is also used to treat certain kinds of heart arrhythmia, such as atrial fibrillation.[2][3]

Contraindications

[edit]Contraindications include[3]

- problems with the heart rhythm, such as severe bradycardia (slow heartbeat), ventricular tachycardia (fast heartbeat caused by the ventricles), ventricular fibrillation, or first- to second-degree atrioventricular block,

- and certain electrolyte imbalances: hypokalemia (low blood potassium levels), hypomagnesemia (low magnesium), and hypercalcemia (high calcium).

Adverse effects and toxicity

[edit]Digitoxin exhibits similar toxic effects to digoxin, namely: anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, confusion, visual disturbances, and cardiac arrhythmias. Antidigoxin antibody fragments, the specific treatment for digoxin poisoning, are also effective in serious digitoxin toxicity.[4]

Interactions

[edit]Drugs that can increase digitoxin toxicity include:[3]

- calcium

- substances that lower potassium or magnesium levels, such as diuretics and corticosteroids

- inhibitors of the liver enzyme CYP3A4, which slow down digitoxin metabolism; examples are the antibiotic clarithromycin, the antifungal itraconazole, and grapefruit juice

- inhibitors of the transporter protein P-gp, such as clarithromycin

- Beta blockers add to the bradycardia (slow heartbeat) caused by digitoxin.

Drugs that can decrease the effectivity of digitoxin include:[3]

- substances that increase potassium levels, such as potassium sparing diuretics

- inducers of CYP3A4 or P-gp, such as phenytoin, rifampicin and St John's Wort

- substances that bind digitoxin in the gut, such as aluminium containing antacids or colestyramine

Pharmacology

[edit]Mechanism of action

[edit]Digitoxin inhibits the sodium-potassium ATPase in heart muscle cells, resulting in increased force of contractions (positive inotropic), reduced speed of electric conduction (negative dromotropic), increased excitability (positive bathmotropic), and reduced frequency of heartbeat (negative chronotropic).[3]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]The drug is almost completely absorbed from the gut. When in the bloodstream, 90 to 97% are bound to plasma proteins. Digitoxin undergoes enterohepatic circulation. It is metabolized in part by CYP3A4; metabolites include digitoxigenin, digoxin (>2%), and conjugate esters. In healthy people, 60% are eliminated via the kidneys and 40% via the faeces. In people with impaired kidney function, elimination via the faeces is increased. The biological half-life is 7 to 8 days except when kidney and liver functions are impaired, in which case it is usually longer.[3][5]

History

[edit]The first description of the use of foxglove dates back to 1775.[6] For quite some time, the active compound was not isolated. Oswald Schmiedeberg was able to obtain a pure sample in 1875. The modern therapeutic use of this molecule was made possible by the works of the pharmacist and the French chemist Claude-Adolphe Nativelle (1812–1889). The first structural analysis was done by Adolf Otto Reinhold Windaus in 1925, but the full structure with an exact determination of the sugar groups was not accomplished until 1962.[7][8]

Use as a weapon

[edit]Digitoxin has been used for at least 7,000 years as an arrow poison.[9] Marie Alexandrine Becker, a Belgian serial killer, was sentenced to death for poisoning eleven people with digitoxin.[citation needed]

In fiction

[edit]Digitoxin is used as a poison or murder weapon in:

- Agatha Christie's Appointment with Death

- Elizabeth Peters' Die For Love

- CSI, season 9, episode 19: "The Descent of Man"

- Rosewood season 2, episode 20: Calliphoridae and Country Roads

- "Casino Royale" (2006)

- "Uneasy Lies the Crown" on Columbo, season 9, episode 5 (1990)

- "Affair of the Heart" on McMillan and Wife, season 6, episode 5 (1977)

- Murder 101: "College can be a Murder"

- Several episodes of Murder She Wrote.

- Private Practice, season 4, episode 18: “The Hardest Part”

In The Decemberists's song, "The Rake's Song" on The Hazards of Love album, the narrator murders his daughter by feeding her foxglove.

In Metal gear Solid V the phantom pain, venom snake uses digitalis to obtain digoxin for tranquilizer rounds to incapacitate enemies.

Research

[edit]Digitoxin and related cardenolides display anticancer activity against a range of human cancer cell lines in vitro but the clinical use of digitoxin to treat cancer has been restricted by its narrow therapeutic index.[10][11] Digitoxin glycorandomization led to the discovery of novel digitoxigenin neoglycosides which displayed improved anticancer potency and reduced inotropic activity (the perceived mechanism of general toxicity).[12]

References

[edit]- ^ Belz GG, Breithaupt-Grögler K, Osowski U (2001). "Treatment of congestive heart failure--current status of use of digitoxin". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 31 (Suppl 2): 10–7. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.0310s2010.x (inactive 9 December 2024). PMID 11525233. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2024 (link) - ^ Erland Erdmann, ed. (2013). Therapie mit Herzglykosiden (in German). Springer. p. 43. ISBN 978-3-642-69046-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Haberfeld H, ed. (2021). Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. Digimerck 0,07 mg - Tabletten.

- ^ Kurowski V, Iven H, Djonlagic H (1992). "Treatment of a patient with severe digitoxin intoxication by Fab fragments of anti-digitalis antibodies". Intensive Care Medicine. 18 (7): 439–42. doi:10.1007/BF01694351. PMID 1469187. S2CID 2324996.

- ^ "mediQ: Digitoxin". Retrieved 2021-09-14.

- ^ Withering W (1785). An Account of the Foxglove and Some of its Medical Uses: With Practical Remarks on Dropsy and other Diseases. Classics of Medicine Library.

- ^ Diefenbach WC, Meneely JK (May 1949). "Digitoxin; a critical review". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 21 (5): 421–31. PMC 2598854. PMID 18127991.

- ^ Sneader W (2005). Drug discovery: A history. Wiley. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-471-89980-8.

- ^ Bradfield, Justin (January 23, 2025). "Discovery in South Africa holds oldest evidence of mixing ingredients to make arrow poison". The Conversation. Retrieved January 24, 2025.

- ^ Menger L, Vacchelli E, Kepp O, Eggermont A, Tartour E, Zitvogel L, et al. (February 2013). "Trial watch: Cardiac glycosides and cancer therapy". Oncoimmunology. 2 (2): e23082. doi:10.4161/onci.23082. PMC 3601180. PMID 23525565.

- ^ Elbaz HA, Stueckle TA, Tse W, Rojanasakul Y, Dinu CZ (April 2012). "Digitoxin and its analogs as novel cancer therapeutics". Experimental Hematology & Oncology. 1 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/2162-3619-1-4. PMC 3506989. PMID 23210930.

- ^ Langenhan JM, Peters NR, Guzei IA, Hoffmann FM, Thorson JS (August 2005). "Enhancing the anticancer properties of cardiac glycosides by neoglycorandomization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (35): 12305–10. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10212305L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503270102. PMC 1194917. PMID 16105948.

Further reading

[edit]- Johansson S, Lindholm P, Gullbo J, Larsson R, Bohlin L, Claeson P (June 2001). "Cytotoxicity of digitoxin and related cardiac glycosides in human tumor cells". Anti-Cancer Drugs. 12 (5): 475–83. doi:10.1097/00001813-200106000-00009. PMID 11395576. S2CID 19894541.

- Hippius M, Humaid B, Sicker T, Hoffmann A, Göttler M, Hasford J (August 2001). "Adverse drug reaction monitoring--digitoxin overdosage in the elderly". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 39 (8): 336–43. doi:10.5414/cpp39336. PMID 11515708.

- Haux J, Klepp O, Spigset O, Tretli S (2001). "Digitoxin medication and cancer; case control and internal dose-response studies". BMC Cancer. 1: 11. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-1-11. PMC 48150. PMID 11532201.

- Srivastava M, Eidelman O, Zhang J, Paweletz C, Caohuy H, Yang Q, et al. (May 2004). "Digitoxin mimics gene therapy with CFTR and suppresses hypersecretion of IL-8 from cystic fibrosis lung epithelial cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (20): 7693–8. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.7693S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0402030101. PMC 419668. PMID 15136726.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Digitoxin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Digitoxin at Wikimedia Commons

- Comparing the Toxicity of Digoxin and Digitoxin in a Geriatric Population: Should an Old Drug Be Rediscovered? on Medscape (registration required), a convenience link from the original. (subscription required)