Fractal dimension

In mathematics, a fractal dimension is a term invoked in the science of geometry to provide a rational statistical index of complexity detail in a pattern. A fractal pattern changes with the scale at which it is measured. It is also a measure of the space-filling capacity of a pattern, and it tells how a fractal scales differently, in a fractal (non-integer) dimension.[1][2][3]

The main idea of "fractured" dimensions has a long history in mathematics, but the term itself was brought to the fore by Benoit Mandelbrot based on his 1967 paper on self-similarity in which he discussed fractional dimensions.[4] In that paper, Mandelbrot cited previous work by Lewis Fry Richardson describing the counter-intuitive notion that a coastline's measured length changes with the length of the measuring stick used (see Fig. 1). In terms of that notion, the fractal dimension of a coastline quantifies how the number of scaled measuring sticks required to measure the coastline changes with the scale applied to the stick.[5] There are several formal mathematical definitions of fractal dimension that build on this basic concept of change in detail with change in scale: see the section Examples.

Ultimately, the term fractal dimension became the phrase with which Mandelbrot himself became most comfortable with respect to encapsulating the meaning of the word fractal, a term he created. After several iterations over years, Mandelbrot settled on this use of the language: "...to use fractal without a pedantic definition, to use fractal dimension as a generic term applicable to all the variants."[6]

One non-trivial example is the fractal dimension of a Koch snowflake. It has a topological dimension of 1, but it is by no means rectifiable: the length of the curve between any two points on the Koch snowflake is infinite. No small piece of it is line-like, but rather it is composed of an infinite number of segments joined at different angles. The fractal dimension of a curve can be explained intuitively by thinking of a fractal line as an object too detailed to be one-dimensional, but too simple to be two-dimensional.[7] Therefore, its dimension might best be described not by its usual topological dimension of 1 but by its fractal dimension, which is often a number between one and two; in the case of the Koch snowflake, it is approximately 1.2619.

Introduction

[edit]

A fractal dimension is an index for characterizing fractal patterns or sets by quantifying their complexity as a ratio of the change in detail to the change in scale.[5]: 1 Several types of fractal dimension can be measured theoretically and empirically (see Fig. 2).[3][9] Fractal dimensions are used to characterize a broad spectrum of objects ranging from the abstract[1][3] to practical phenomena, including turbulence,[5]: 97–104 river networks,: 246–247 urban growth,[10][11] human physiology,[12][13] medicine,[9] and market trends.[14] The essential idea of fractional or fractal dimensions has a long history in mathematics that can be traced back to the 1600s,[5]: 19 [15] but the terms fractal and fractal dimension were coined by mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot in 1975.[1][2][5][9][14][16]

Fractal dimensions were first applied as an index characterizing complicated geometric forms for which the details seemed more important than the gross picture.[16] For sets describing ordinary geometric shapes, the theoretical fractal dimension equals the set's familiar Euclidean or topological dimension. Thus, it is 0 for sets describing points (0-dimensional sets); 1 for sets describing lines (1-dimensional sets having length only); 2 for sets describing surfaces (2-dimensional sets having length and width); and 3 for sets describing volumes (3-dimensional sets having length, width, and height). But this changes for fractal sets. If the theoretical fractal dimension of a set exceeds its topological dimension, the set is considered to have fractal geometry.[17]

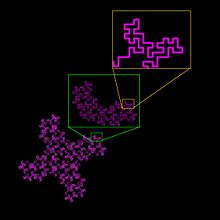

Unlike topological dimensions, the fractal index can take non-integer values,[18] indicating that a set fills its space qualitatively and quantitatively differently from how an ordinary geometrical set does.[1][2][3] For instance, a curve with a fractal dimension very near to 1, say 1.10, behaves quite like an ordinary line, but a curve with fractal dimension 1.9 winds convolutedly through space very nearly like a surface. Similarly, a surface with fractal dimension of 2.1 fills space very much like an ordinary surface, but one with a fractal dimension of 2.9 folds and flows to fill space rather nearly like a volume.[17]: 48 [notes 1] This general relationship can be seen in the two images of fractal curves in Fig.2 and Fig. 3 – the 32-segment contour in Fig. 2, convoluted and space filling, has a fractal dimension of 1.67, compared to the perceptibly less complex Koch curve in Fig. 3, which has a fractal dimension of approximately 1.2619.

The relationship of an increasing fractal dimension with space-filling might be taken to mean fractal dimensions measure density, but that is not so; the two are not strictly correlated.[8] Instead, a fractal dimension measures complexity, a concept related to certain key features of fractals: self-similarity and detail or irregularity.[notes 2] These features are evident in the two examples of fractal curves. Both are curves with topological dimension of 1, so one might hope to be able to measure their length and derivative in the same way as with ordinary curves. But we cannot do either of these things, because fractal curves have complexity in the form of self-similarity and detail that ordinary curves lack.[5] The self-similarity lies in the infinite scaling, and the detail in the defining elements of each set. The length between any two points on these curves is infinite, no matter how close together the two points are, which means that it is impossible to approximate the length of such a curve by partitioning the curve into many small segments.[19] Every smaller piece is composed of an infinite number of scaled segments that look exactly like the first iteration. These are not rectifiable curves, meaning they cannot be measured by being broken down into many segments approximating their respective lengths. They cannot be meaningfully characterized by finding their lengths and derivatives. However, their fractal dimensions can be determined, which shows that both fill space more than ordinary lines but less than surfaces, and allows them to be compared in this regard.

The two fractal curves described above show a type of self-similarity that is exact with a repeating unit of detail that is readily visualized. This sort of structure can be extended to other spaces (e.g., a fractal that extends the Koch curve into 3-d space has a theoretical D=2.5849). However, such neatly countable complexity is only one example of the self-similarity and detail that are present in fractals.[3][14] The example of the coast line of Britain, for instance, exhibits self-similarity of an approximate pattern with approximate scaling.[5]: 26 Overall, fractals show several types and degrees of self-similarity and detail that may not be easily visualized. These include, as examples, strange attractors for which the detail has been described as in essence, smooth portions piling up,[17]: 49 the Julia set, which can be seen to be complex swirls upon swirls, and heart rates, which are patterns of rough spikes repeated and scaled in time.[20] Fractal complexity may not always be resolvable into easily grasped units of detail and scale without complex analytic methods but it is still quantifiable through fractal dimensions.[5]: 197, 262

History

[edit]The terms fractal dimension and fractal were coined by Mandelbrot in 1975,[16] about a decade after he published his paper on self-similarity in the coastline of Britain. Various historical authorities credit him with also synthesizing centuries of complicated theoretical mathematics and engineering work and applying them in a new way to study complex geometries that defied description in usual linear terms.[15][21][22] The earliest roots of what Mandelbrot synthesized as the fractal dimension have been traced clearly back to writings about nondifferentiable, infinitely self-similar functions, which are important in the mathematical definition of fractals, around the time that calculus was discovered in the mid-1600s.[5]: 405 There was a lull in the published work on such functions for a time after that, then a renewal starting in the late 1800s with the publishing of mathematical functions and sets that are today called canonical fractals (such as the eponymous works of von Koch,[19] Sierpiński, and Julia), but at the time of their formulation were often considered antithetical mathematical "monsters".[15][22] These works were accompanied by perhaps the most pivotal point in the development of the concept of a fractal dimension through the work of Hausdorff in the early 1900s who defined a "fractional" dimension that has come to be named after him and is frequently invoked in defining modern fractals.[4][5]: 44 [17][21]

See Fractal history for more information

Role of scaling

[edit]

, ,

, ,

, , [23]

The concept of a fractal dimension rests in unconventional views of scaling and dimension.[24] As Fig. 4 illustrates, traditional notions of geometry dictate that shapes scale predictably according to intuitive and familiar ideas about the space they are contained within, such that, for instance, measuring a line using first one measuring stick then another 1/3 its size, will give for the second stick a total length 3 times as many sticks long as with the first. This holds in 2 dimensions, as well. If one measures the area of a square then measures again with a box of side length 1/3 the size of the original, one will find 9 times as many squares as with the first measure. Such familiar scaling relationships can be defined mathematically by the general scaling rule in Equation 1, where the variable stands for the number of measurement units (sticks, squares, etc.), for the scaling factor, and for the fractal dimension:

| (1) |

This scaling rule typifies conventional rules about geometry and dimension – referring to the examples above, it quantifies that for lines because when , and that for squares because when

The same rule applies to fractal geometry but less intuitively. To elaborate, a fractal line measured at first to be one length, when remeasured using a new stick scaled by 1/3 of the old may be 4 times as many scaled sticks long rather than the expected 3 (see Fig. 5). In this case, when and the value of can be found by rearranging Equation 1:

| (2) |

That is, for a fractal described by when , such as the Koch snowflake, , a non-integer value that suggests the fractal has a dimension not equal to the space it resides in.[3]

Of note, images shown in this page are not true fractals because the scaling described by cannot continue past the point of their smallest component, a pixel. However, the theoretical patterns that the images represent have no discrete pixel-like pieces, but rather are composed of an infinite number of infinitely scaled segments and do indeed have the claimed fractal dimensions.[5][24]

D is not a unique descriptor

[edit]

As is the case with dimensions determined for lines, squares, and cubes, fractal dimensions are general descriptors that do not uniquely define patterns.[24][25] The value of D for the Koch fractal discussed above, for instance, quantifies the pattern's inherent scaling, but does not uniquely describe nor provide enough information to reconstruct it. Many fractal structures or patterns could be constructed that have the same scaling relationship but are dramatically different from the Koch curve, as is illustrated in Figure 6.

For examples of how fractal patterns can be constructed, see Fractal, Sierpinski triangle, Mandelbrot set, Diffusion limited aggregation, L-system.

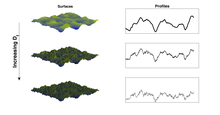

Fractal surface structures

[edit]The concept of fractality is applied increasingly in the field of surface science, providing a bridge between surface characteristics and functional properties.[26] Numerous surface descriptors are used to interpret the structure of nominally flat surfaces, which often exhibit self-affine features across multiple length-scales. Mean surface roughness, usually denoted RA, is the most commonly applied surface descriptor, however numerous other descriptors including mean slope, root mean square roughness (RRMS) and others are regularly applied. It is found however that many physical surface phenomena cannot readily be interpreted with reference to such descriptors, thus fractal dimension is increasingly applied to establish correlations between surface structure in terms of scaling behavior and performance.[27] The fractal dimensions of surfaces have been employed to explain and better understand phenomena in areas of contact mechanics,[28] frictional behavior,[29] electrical contact resistance[30] and transparent conducting oxides.[31]

Examples

[edit]The concept of fractal dimension described in this article is a basic view of a complicated construct. The examples discussed here were chosen for clarity, and the scaling unit and ratios were known ahead of time. In practice, however, fractal dimensions can be determined using techniques that approximate scaling and detail from limits estimated from regression lines over log vs log plots of size vs scale. Several formal mathematical definitions of different types of fractal dimension are listed below. Although for compact sets with exact affine self-similarity all these dimensions coincide, in general they are not equivalent:

- Box counting dimension: D is estimated as the exponent of a power law.

- Information dimension: D considers how the average information needed to identify an occupied box scales with box size; is a probability.

- Correlation dimension: D is based on as the number of points used to generate a representation of a fractal and gε, the number of pairs of points closer than ε to each other.

- Generalized or Rényi dimensions: The box-counting, information, and correlation dimensions can be seen as special cases of a continuous spectrum of generalized dimensions of order α, defined by:

- Lyapunov dimension

- Multifractal dimensions: a special case of Rényi dimensions where scaling behaviour varies in different parts of the pattern.

- Uncertainty exponent

- Hausdorff dimension: For any subset of a metric space and , the d-dimensional Hausdorff content of S is defined by

- The Hausdorff dimension of S is defined by

- Packing dimension

- Assouad dimension

- Local connected dimension[33]

- Degree dimension: describes the fractal nature of the degree distribution of graphs.[34]

Estimating from real-world data

[edit]Many real-world phenomena exhibit limited or statistical fractal properties and fractal dimensions that have been estimated from sampled data using computer based fractal analysis techniques. Practically, measurements of fractal dimension are affected by various methodological issues, and are sensitive to numerical or experimental noise and limitations in the amount of data. Nonetheless, the field is rapidly growing as estimated fractal dimensions for statistically self-similar phenomena may have many practical applications in various fields including astronomy,[35] acoustics,[36][37] geology and earth sciences,[38] diagnostic imaging,[39][40][41] ecology,[42] electrochemical processes,[43] image analysis,[44][45][46][47] biology and medicine,[48][49][50] neuroscience,[51][13] network analysis, physiology,[12] physics,[52][53] and Riemann zeta zeros.[54] Fractal dimension estimates have also been shown to correlate with Lempel-Ziv complexity in real-world data sets from psychoacoustics and neuroscience.[55][36]

An alternative to a direct measurement, is considering a mathematical model that resembles formation of a real-world fractal object. In this case, a validation can also be done by comparing other than fractal properties implied by the model, with measured data. In colloidal physics, systems composed of particles with various fractal dimensions arise. To describe these systems, it is convenient to speak about a distribution of fractal dimensions, and eventually, a time evolution of the latter: a process that is driven by a complex interplay between aggregation and coalescence.[56]

See also

[edit]- List of fractals by Hausdorff dimension

- Lacunarity – Term in geometry and fractal analysis

- Fractal derivative – Generalization of derivative to fractals

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Falconer, Kenneth (2003). Fractal Geometry. Wiley. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-470-84862-3.

- ^ a b c Sagan, Hans (1994). Space-Filling Curves. Springer-Verlag. p. 156. ISBN 0-387-94265-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Vicsek, Tamás (1992). Fractal growth phenomena. World Scientific. p. 10. ISBN 978-981-02-0668-0.

- ^ a b Mandelbrot, B. (1967). "How Long is the Coast of Britain? Statistical Self-Similarity and Fractional Dimension". Science. 156 (3775): 636–8. Bibcode:1967Sci...156..636M. doi:10.1126/science.156.3775.636. PMID 17837158. S2CID 15662830. Archived from the original on 2021-10-19. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Benoit B. Mandelbrot (1983). The fractal geometry of nature. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7167-1186-5. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ^ Edgar, Gerald (2007). Measure, Topology, and Fractal Geometry. Springer. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-387-74749-1.

- ^ Harte, David (2001). Multifractals. Chapman & Hall. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-1-58488-154-4.

- ^ a b c Balay-Karperien, Audrey (2004). Defining Microglial Morphology: Form, Function, and Fractal Dimension. Charles Sturt University. p. 86. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ a b c Losa, Gabriele A.; Nonnenmacher, Theo F., eds. (2005). Fractals in biology and medicine. Springer. ISBN 978-3-7643-7172-2. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ^ Chen, Yanguang (2011). "Modeling Fractal Structure of City-Size Distributions Using Correlation Functions". PLOS ONE. 6 (9): e24791. arXiv:1104.4682. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...624791C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024791. PMC 3176775. PMID 21949753.

- ^ "Applications". Archived from the original on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2007-10-21.

- ^ a b Popescu, D. P.; Flueraru, C.; Mao, Y.; Chang, S.; Sowa, M. G. (2010). "Signal attenuation and box-counting fractal analysis of optical coherence tomography images of arterial tissue". Biomedical Optics Express. 1 (1): 268–277. doi:10.1364/boe.1.000268. PMC 3005165. PMID 21258464.

- ^ a b King, R. D.; George, A. T.; Jeon, T.; Hynan, L. S.; Youn, T. S.; Kennedy, D. N.; Dickerson, B.; the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2009). "Characterization of Atrophic Changes in the Cerebral Cortex Using Fractal Dimensional Analysis". Brain Imaging and Behavior. 3 (2): 154–166. doi:10.1007/s11682-008-9057-9. PMC 2927230. PMID 20740072.

- ^ a b c Peters, Edgar (1996). Chaos and order in the capital markets : a new view of cycles, prices, and market volatility. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-13938-6.

- ^ a b c Edgar, Gerald, ed. (2004). Classics on Fractals. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-4153-8.

- ^ a b c Albers; Alexanderson (2008). "Benoit Mandelbrot: In his own words". Mathematical people : profiles and interviews. AK Peters. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-56881-340-0.

- ^ a b c d

Mandelbrot, Benoit (2004). Fractals and Chaos. Springer. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-387-20158-0.

A fractal set is one for which the fractal (Hausdorff-Besicovitch) dimension strictly exceeds the topological dimension

- ^ Sharifi-Viand, A.; Mahjani, M. G.; Jafarian, M. (2012). "Investigation of anomalous diffusion and multifractal dimensions in polypyrrole film". Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 671: 51–57. doi:10.1016/j.jelechem.2012.02.014.

- ^ a b Helge von Koch, "On a continuous curve without tangents constructible from elementary geometry" In Edgar 2004, pp. 25–46

- ^ Tan, Can Ozan; Cohen, Michael A.; Eckberg, Dwain L.; Taylor, J. Andrew (2009). "Fractal properties of human heart period variability: Physiological and methodological implications". The Journal of Physiology. 587 (15): 3929–41. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2009.169219. PMC 2746620. PMID 19528254.

- ^ a b Gordon, Nigel (2000). Introducing fractal geometry. Duxford: Icon. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-84046-123-7.

- ^ a b Trochet, Holly (2009). "A History of Fractal Geometry". MacTutor History of Mathematics. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012.

- ^ Appignanesi, Richard; ed. (2006). Introducing Fractal Geometry, p.28. Icon. ISBN 978-1840467-13-0.

- ^ a b c Iannaccone, Khokha (1996). Fractal Geometry in Biological Systems. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-7636-8.

- ^ Vicsek, Tamás (2001). Fluctuations and scaling in biology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850790-9.

- ^ Pfeifer, Peter (1988), "Fractals in Surface Science: Scattering and Thermodynamics of Adsorbed Films", in Vanselow, Ralf; Howe, Russell (eds.), Chemistry and Physics of Solid Surfaces VII, Springer Series in Surface Sciences, vol. 10, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 283–305, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-73902-6_10, ISBN 9783642739040

- ^ Milanese, Enrico; Brink, Tobias; Aghababaei, Ramin; Molinari, Jean-François (December 2019). "Emergence of self-affine surfaces during adhesive wear". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 1116. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.1116M. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09127-8. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6408517. PMID 30850605.

- ^ Contact stiffness of multiscale surfaces, In the International Journal of Mechanical Sciences (2017), 131

- ^ Static Friction at Fractal Interfaces, Tribology International (2016), vol 93

- ^ Chongpu, Zhai; Dorian, Hanaor; Gwénaëlle, Proust; Yixiang, Gan (2017). "Stress-Dependent Electrical Contact Resistance at Fractal Rough Surfaces". Journal of Engineering Mechanics. 143 (3): B4015001. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)EM.1943-7889.0000967.

- ^ Kalvani, Payam Rajabi; Jahangiri, Ali Reza; Shapouri, Samaneh; Sari, Amirhossein; Jalili, Yousef Seyed (August 2019). "Multimode AFM analysis of aluminum-doped zinc oxide thin films sputtered under various substrate temperatures for optoelectronic applications". Superlattices and Microstructures. 132: 106173. doi:10.1016/j.spmi.2019.106173. S2CID 198468676.

- ^ Higuchi, T. (1988). "Approach to an irregular time-series on the basis of the fractal theory". Physica D. 31 (2): 277–283. Bibcode:1988PhyD...31..277H. doi:10.1016/0167-2789(88)90081-4.

- ^ Jelinek, A.; Jelinek, H. F.; Leandro, J. J.; Soares, J. V.; Cesar Jr, R. M.; Luckie, A. (2008). "Automated detection of proliferative retinopathy in clinical practice". Clinical Ophthalmology. 2 (1): 109–122. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S1579. PMC 2698675. PMID 19668394.

- ^ Li, N. Z.; Britz, T. (2024). "On the scale-freeness of random colored substitution networks". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 152 (4): 1377–1389. arXiv:2109.14463. doi:10.1090/proc/16604.

- ^ Caicedo-Ortiz, H. E.; Santiago-Cortes, E.; López-Bonilla, J.; Castañeda4, H. O. (2015). "Fractal dimension and turbulence in Giant HII Regions". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 582 (1): 1–5. arXiv:1501.04911. Bibcode:2015JPhCS.582a2049C. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/582/1/012049.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Burns, T.; Rajan, R. (2019). "A Mathematical Approach to Correlating Objective Spectro-Temporal Features of Non-linguistic Sounds With Their Subjective Perceptions in Humans". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 13: 794. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.00794. PMC 6685481. PMID 31417350.

- ^ Maragos, P.; Potamianos, A. (1999). "Fractal dimensions of speech sounds: Computation and application to automatic speech recognition". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 105 (3): 1925–32. Bibcode:1999ASAJ..105.1925M. doi:10.1121/1.426738. PMID 10089613.

- ^ Avşar, Elif (2020-09-01). "Contribution of fractal dimension theory into the uniaxial compressive strength prediction of a volcanic welded bimrock". Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment. 79 (7): 3605–3619. Bibcode:2020BuEGE..79.3605A. doi:10.1007/s10064-020-01778-y. ISSN 1435-9537. S2CID 214648440.

- ^ Landini, G.; Murray, P. I.; Misson, G. P. (1995). "Local connected fractal dimensions and lacunarity analyses of 60 degrees fluorescein angiograms". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 36 (13): 2749–2755. PMID 7499097.

- ^ Cheng, Qiuming (1997). "Multifractal Modeling and Lacunarity Analysis". Mathematical Geology. 29 (7): 919–932. Bibcode:1997MatG...29..919C. doi:10.1023/A:1022355723781. S2CID 118918429.

- ^ Santiago-Cortés, E.; Martínez Ledezma, J. L. (2016). "Fractal dimension in human retinas" (PDF). Journal de Ciencia e Ingeniería. 8: 59–65. eISSN 2539-066X. ISSN 2145-2628.

- ^ Wildhaber, Mark L.; Lamberson, Peter J.; Galat, David L. (2003-05-01). "A Comparison of Measures of Riverbed Form for Evaluating Distributions of Benthic Fishes". North American Journal of Fisheries Management. 23 (2): 543–557. Bibcode:2003NAJFM..23..543W. doi:10.1577/1548-8675(2003)023<0543:acomor>2.0.co;2. ISSN 1548-8675.

- ^ Eftekhari, A. (2004). "Fractal Dimension of Electrochemical Reactions". Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 151 (9): E291–6. Bibcode:2004JElS..151E.291E. doi:10.1149/1.1773583.

- ^ Al-Kadi O.S, Watson D. (2008). "Texture Analysis of Aggressive and non-Aggressive Lung Tumor CE CT Images" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 55 (7): 1822–30. doi:10.1109/tbme.2008.919735. PMID 18595800. S2CID 14784161. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-13. Retrieved 2014-04-10.

- ^ Pierre Soille and Jean-F. Rivest (1996). "On the Validity of Fractal Dimension Measurements in Image Analysis" (PDF). Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation. 7 (3): 217–229. doi:10.1006/jvci.1996.0020. ISSN 1047-3203. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-20.

- ^ Tolle, C. R.; McJunkin, T. R.; Gorsich, D. J. (2003). "Suboptimal minimum cluster volume cover-based method for measuring fractal dimension". IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 25: 32–41. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.79.6978. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2003.1159944.

- ^ Gorsich, D. J.; Tolle, C. R.; Karlsen, R. E.; Gerhart, G. R. (1996). "Wavelet and fractal analysis of ground-vehicle images". In Unser, Michael A.; Aldroubi, Akram; Laine, Andrew F. (eds.). Wavelet Applications in Signal and Image Processing IV. Proceedings of the SPIE. Vol. 2825. pp. 109–119. Bibcode:1996SPIE.2825..109G. doi:10.1117/12.255224. S2CID 121560110.

- ^ Liu, Jing Z.; Zhang, Lu D.; Yue, Guang H. (2003). "Fractal Dimension in Human Cerebellum Measured by Magnetic Resonance Imaging". Biophysical Journal. 85 (6): 4041–6. Bibcode:2003BpJ....85.4041L. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74817-6. PMC 1303704. PMID 14645092.

- ^ Smith, T. G.; Lange, G. D.; Marks, W. B. (1996). "Fractal methods and results in cellular morphology — dimensions, lacunarity and multifractals". Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 69 (2): 123–136. doi:10.1016/S0165-0270(96)00080-5. PMID 8946315. S2CID 20175299.

- ^ Li, J.; Du, Q.; Sun, C. (2009). "An improved box-counting method for image fractal dimension estimation". Pattern Recognition. 42 (11): 2460–9. Bibcode:2009PatRe..42.2460L. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2009.03.001.

- ^ Burns, T.; Rajan, R. (2015). "Burns & Rajan (2015) Combining complexity measures of EEG data: multiplying measures reveal previously hidden information. F1000Research. 4:137". F1000Research. 4: 137. doi:10.12688/f1000research.6590.1. PMC 4648221. PMID 26594331.

- ^ Dubuc, B.; Quiniou, J.; Roques-Carmes, C.; Tricot, C.; Zucker, S. (1989). "Evaluating the fractal dimension of profiles". Physical Review A. 39 (3): 1500–12. Bibcode:1989PhRvA..39.1500D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.39.1500. PMID 9901387.

- ^ Roberts, A.; Cronin, A. (1996). "Unbiased estimation of multi-fractal dimensions of finite data sets". Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications. 233 (3–4): 867–878. arXiv:chao-dyn/9601019. Bibcode:1996PhyA..233..867R. doi:10.1016/S0378-4371(96)00165-3. S2CID 14388392.

- ^ Shanker, O. (2006). "Random matrices, generalized zeta functions and self-similarity of zero distributions". Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General. 39 (45): 13983–97. Bibcode:2006JPhA...3913983S. doi:10.1088/0305-4470/39/45/008.

- ^ Burns, T.; Rajan, R. (2015). "Burns & Rajan (2015) Combining complexity measures of EEG data: multiplying measures reveal previously hidden information. F1000Research. 4:137". F1000Research. 4: 137. doi:10.12688/f1000research.6590.1. PMC 4648221. PMID 26594331.

- ^ Kryven, I.; Lazzari, S.; Storti, G. (2014). "Population Balance Modeling of Aggregation and Coalescence in Colloidal Systems". Macromolecular Theory and Simulations. 23 (3): 170–181. doi:10.1002/mats.201300140.

Further reading

[edit]- Mandelbrot, Benoit B.; Hudson, Richard L. (2010). The (Mis)Behaviour of Markets: A Fractal View of Risk, Ruin and Reward. Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-84765-155-6.

External links

[edit]- TruSoft's Benoit, fractal analysis software product calculates fractal dimensions and hurst exponents.

- A Java Applet to Compute Fractal Dimensions

- Introduction to Fractal Analysis

- Bowley, Roger (2009). "Fractal Dimension". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.

- "Fractals are typically not self-similar". 3Blue1Brown.